Matir Asurim Torah Explorations

Full Sivan 5783 Divrei Matir Asurim available via Archive.org (visit Dec 2024 archived version)

Divrei Matir Asurim was a monthly publication of Matir Asurim: Jewish Care Network for Incarcerated People and available in three formats: straight text for copying into emails; formatted text for copying/printing for postal mail; and on-line (with some internet links for those who can access them). If these are not accessible, PDFs can be uploaded to this page directly — please advise if there is a need.

Re-sharing here for easy access; intended for sharing with people experiencing incarceration or re-entry who seek Jewish spiritual support. Unless otherwise noted, writing is by Virginia Avniel Spatz; most material is published with CC-BY-SA [creative commons-attribution-share alike] license, unless otherwise noted.

Dates updated for 2025 and 5785. New links, via Archive and other sources, updated due to stalled renovation of Matir Asurim website. Otherwise material is as it was published originally.

Launching New Journeys

There are many ways to read Torah and other Jewish texts. We hope this section will offer different approaches. The two offering for this edition are built on the idea that we are all connected to the Torah.

The long Exodus and wilderness journey are a huge part of the Torah story. That story is tangled up with Jewish history and with our lives today. So, we can learn new things about the Torah by linking it with our own stories. And Torah can give us new ways of thinking about our own lives.

The wilderness story is about a group of people learning to be a community in very difficult circumstances. The story emphasizes groups and crowds:

Who is part of which group?

How does that change?

And what, if anything, do a person’s groups tell us about them as a person?

How do individuals change groups and crowds?

The Book of Numbers

The fourth book of the Torah begins with a census. In English, the book is called “Numbers.” In Hebrew, the name is “Bamidbar, which means“in the wilderness” or “in the desert.”

Both titles tell us a little about what is in the book.

Numbers:

— counting

— naming

— boundaries

In the Wilderness:

— journeying

— confusion

— living in-between

Numbers/Wildernessasks us to think about individuals and communities, and how the two affect each other.

The previous book, Leviticus (Vayikra), focused on ritual without much story. Numbers returns to the Exodus story. It continues to follow a large group of people who, just months before, escaped from Mitzrayim, biblical Egypt. The big group in the wilderness includes Israelites, who were enslaved, and many other people who fled tyranny along with them.

In Numbers, the community complains a lot. And they disagree with the brother leaders, Moses and Aaron. This happened in Exodus, too. But the book of Numbers emphasizes how hard it is for God, the leaders, and the community to understand and trust each other.

The people already survived slavery and plagues and being chased by Pharaoh’s army. They had some powerful, frightening experiences at Mount Sinai. And now, at the beginning of this new book, the challenges are just starting….

In the Wilderness/Bamidbar

Bamidbar [In the Wilderness] Num 1:1- 4:20.

In the first chapter, God tells Moses to “assemble” everyone. Moses and Aaron tell the men to line up and state their family name and history.

Some men are “pointed out by name.” Others are lumped in with just a family name. Only men are named. And the family line is emphasized.

Sometimes we are “pointed out by name.” For better or for worse.

Sometimes we are left out of the story, for one reason or another.

How does it feel to be named? Counted?

How does it feel to be left out?

How does it feel to be identified by a group name instead of our own?

How does it feel to be part of a crowd not of our own choosing?

Turns out: Men 20+ years old are being counted as ones who can “go out in war.” Before this, the people knew there were dangers ahead. They were already attacked on the way, back in Exodus. But this is the first mention of preparing for war. And the people still don’t know where they’re going — only that Moses says that God has a plan.

The book just started, and already we’re in pretty deep. Seem familiar? Maybe we’re always “in the Wilderness.”

A Little Deeper into the Wilderness

The word used to “point out” people by name, at the beginning of Numbers (1:17), is one connected with danger. Being “pointed out” seems like a complicated and serious matter.

…The verb, nikvu, is from a root meaning “pierce” or “puncture,” as well as “point out” or “designate.” The same word is used (Lev 24:16) for pronouncing the sacred name: “piercing God’s Name [v’nokeiv shem-YHVH]….

The verb used when the community “was assembled” also carries different values. Here in chapter 1, the “entire community” gathers for this census. This seems to be a positive action. God commanded it, an there is no argument or negativity involved.

…The verb “was assembled [הִקְהִילוּ, hikhilu]” is from a root (kaf-hey-lamed, קהל) with different values in different contexts….

SPOILER ALERT!! Jumping ahead to Numbers 16. The same verb is used later when cousins of Moses and Aaron “assemble” in uprising. This ends very badly. And it’s not the only serious conflict to come. There are fights over leadership and many divisions of the people. But this isn’t the whole story either.

Beyond the Wilderness

In addition to weekly Torah portions, the reading cycle includes verses from the Prophets, called the “haftarah reading.” The haftarah reading for Bamidbar is Hosea 2:1-22.

The passage begins:

The number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea, which cannot be measured nor numbered…’You are the children of the Living God.’

— Hosea 2:1

This verse lifts us out of the Torah story and our own. It suggests a future when divisions no longer matter, a time when everyone merges into relationship with “the Living God.”

Does a vision like this one from Hosea change how we read the Torah story?

Does it change the way we read our own stories?

Naso: Census/Lift Up

Naso [Take a Census/Lift Up]: Num 4:21-7:89.

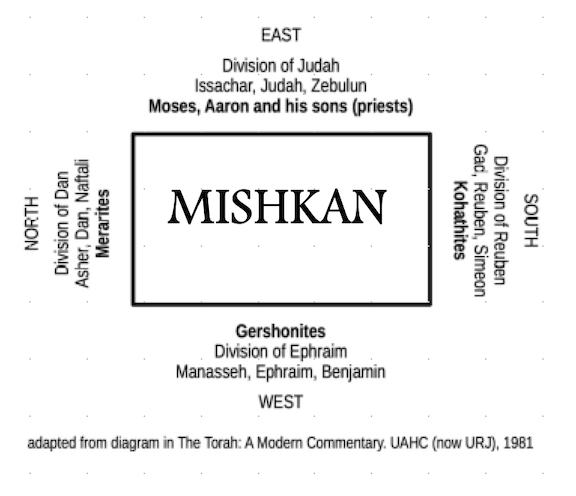

This portion includes more census, this time for tribes with special ritual responsibilities. The clans counted are Gershonites and Merarites. Kohathites were already counted. All three clans are responsible for the Mishkan, the portable sanctuary carried through the wilderness. These clans, all Levites, do not fight in wars. Instead, they serve the Mishkan for twenty years (age 30-50). This portion lists their duties and where each clan camps.

…Gershon, Kohath, and Merari were sons of Levy, third son of Jacob/Yisrael. So these clans are all in the Levite tribe.

“Gershon” ~ “exile” or “stranger.” “Kohath” ~ “assembly.” “Merari” ~ “bitter.”…

The Levites camp closest to the Mishkan.East is the “first” direction for the Torah, so Moses and Aaron and the priests are in a place of the most privilege. They also have the biggest responsibility.

Do rigid rules about a person’s place help preserve order?

Or create bad feelings?

Can assigned places help someone feel they belong?

How does assigning places relate to “having someone’s number”?

Judaism is very careful about counting people. For example, there are many customs to check if a minyan of ten is present withOUT counting. This census was commanded by God, but Jewish teaching still treats it as a dangerous activity.

In- and outside Judaism, many people are sensitive about telling someone’s age and other identifying information. “Having someone’s number” means having a kind of power over them. Today, IDs and credit card numbers are protected to avoid fraud. They are also regularly demanded by businesses and government institutions. Some of us are constantly identified by a numbers.

Camp image description: Center is rectangle labeled “Mishkan.” EAST: outside: Division of Judah; then: Issachar, Judah, Zebulun; inside: Moses, Aaron and his sons (priests). SOUTH: outside: Division of Reuben; then: Gad, Reuben, Simeon; inside: Kohathites. WEST: outside: Manasseh, Ephraim, Benjamin; then: Division of Ephraim; inside: Gershonites. NORTH: outside: Division of Dan; then: Asher, Dan, Naftali; inside: Merarites.

———————

The Priestly Blessing

Near the end of the portion, Naso, is one of the most famous passages in the bible, called “The Priestly Blessing (Birkat Kohanim).”

The Priestly Blessing has been part of Jewish prayer services for centuries. Some custom uses only the first three lines — “May GOD…” — in prayers. Some include the fourth (“Put My name…”) as well.

Here is the passage in English (Num 6:22-27), followed by the blessing verses (24-27) again in Hebrew:

(22) GOD spoke to Moses saying: (23) Speak to Aaron and his sons saying: Thus you shall bless the people of Israel. Say to them:

(24) May GOD bless you and watch over you!

(25) May GOD shine [Their] face toward you and favor you!

(26) May GOD lift up [Their] face toward you and grant you shalom!

(27) Put My name upon the Children of Israel, that I myself may bless them.

Y’varekhekha YHVH v’yishm’rekha

Yaeir YHVH panav elekha v’chunekha

Yisa YHVH panav elekha v’yaseim lekha shalom

V’samu et-sh’mi al-bnei yisrael va’ani avarkhem

In the Torah setting out in the wilderness, the blessing goes out in a widening pattern:

God spoke to Moses;

Moses says to Aaron and sons;

The priests (Aaron and sons) bless the people.

Commentary also explains that the priests bless the people and THEN God blesses the priests. (Babylonian Talmud, Chullin 49a). So the blessing seems to flow in several directions. It is meant to be shared. And it seems that humans have roles in sharing it.

Practice of Blessing

There are many musical settings for the Priestly Blessing, in Hebrew and English and other languages. Other music, including Bob Dylan’s “Forever Young,” is inspired by these words.

Jews use the blessing today, during informal and formal prayers. Practice depends on how Jewish communities understand “priesthood.”

Some Jewish communities today continue to recognize Jews in three categories:

- Cohen — descendants of priests,

- Levy — descendants of other Levites,

- Yisrael — Jews of other lineage.

This distinction matters, for ritual and other reasons. But many Jews no longer recognize these differences at all.

Some Jewish movements specifically stress, instead, that we are all “a community of priests” (Exodus 19:6). In some Jewish communities, the Priestly Blessing is recited only by Cohanim, male descendants of the priestly line, with assistance from men of the line of Levy. In others, practice during regular and holiday prayers varies. Some congregations recite the words of Torah (above) as part of the liturgy, but do not ask anyone to bless others. Some have the whole community share blessings with those in- and outside the room where prayers are taking place. In addition, some communities today make creative use of the pattern in the Priestly Blessing to consider how we can all share and experience blessing.

Some contemporary practices related to Priestly Blessing:

Focus on sending blessing (by yourself or in a group):

- first to those known or nearest

- then to more distant or unknown neighbors,

- finally, the blessing is sent out the wider world

Focus on blessing for repair and strengthening relationship (by yourself):

- first to a loved one, with whom you have a good relationship,

- then to a stranger, with whom you have no special relationship,

- finally, to someone with whom you have a problematic relationship

Meditate on (self or group):

- being watched over or guarded

- being graced with God’s face

- “putting God’s name” on someone(s) to facilitate blessing

full Divrei Matir Asurim Sivan 5784 available via Archive.org

Leaving Leviticus

The last portion of the Book of Leviticus is Bechukotai [In my laws] Lev 26:3 – 27:34. It is read, along with Behar Lev 25:1-26:2, on May 24 (26 Iyar) in 2025.. See the discussion on “All Israel Responsible One for Another,” based on a verse in this portion. (See note below.)

See also the discussion of “Jeremiah’s Trees,” from the haftarah** for Bechukotai: Jeremiah 16:19-17:14. (“Trees” BELOW).

Schedule of Torah/Haftarah Readings for Numbers/Bamidbar UPDATED for 5785

Hebrew title [English]. Chapters: verse* Haftarah** Civic date. Hebrew date

Bamidbar[ In the Desert]. Num 1:1-4:20 Hosea 2:1-22 May 31. 4 Sivan

Nasso [Take a Census] Numbers 4:21 – 7:89 Judges 13:2-25 June 7. 11 Sivan

Beha’alotkha [When You Raise] 8:1-12:16 Zechariah 2:14-4:7 June 14. 18 Sivan

Shelakh [“Send”] 13:1-15:41 Joshua 2:2-24 June 21. 25 Sivan

Korach (name) 16:1-18:32 1 Sam 11:14-12-22 June 28. 2 Tamuz

Chukat [“Law of”] 19:1-22:1 Judges 11:1-33 July 5 . 9Tamuz

Balak (name) 22:2-25:9 Micah 5:6-6:8 July 12. 16 Tamuz

Pinchas (name) 25:10 – 30:1 1 Kings 18:46-19:21 July 19. 23 Tamuz

Matot [“Tribes”] 30:2-32:42 / Masei [“Travels”] 33:1-36:13 Jeremiah 2:4-28, 3:4. July 26. 1 Av

*Dates listed are for the Shabbat on which the portion is read. Where daily services are held, verses from the same portion are read on the Monday and Thursday before that Shabbat. These are listings for a full Torah reading each week, completing the Torah in one year. There is also a custom of splitting the Torah portion into three sections for the public reading; in the “triennial cycle,” the entire Torah cycle is completed each year, but only one-third of each portion is read aloud in any given year: the first year, section one; the next year, second two; the third year, section three.

**The haftarah [plural: haftarot] is a reading from the Prophets linked to each week’s Torah reading. This is a very old tradition, and verses vary a little across communities. These are Ashkenazi listings, based on completing the full Torah in one year, the most common practice in the US and Canada. Sephardic, Yemeni, and some other customs vary from the above. In addition, some communities use alternate readings to match the triennial [three-year] reading cycle, lifting up a theme from the section read that year. A few Jewish communities choose another reading entirely for philosophical reasons.

TORAH EXPLORATIONS: Guiding Concepts

This section of Divrei Matir Asurim is taken from this website page.

Follow links on the About Matir Asurim page to learn more about the six Guiding Concepts in Jewish thought, as developed in consultation between inside and outside members.

TORAH EXPLORATIONS: Jeremiah’s Trees

[Related, somewhat overlapping piece on this site at “Abundance and Need.”]

A famous passage in the Book of Jeremiah speaks of two plants:

- a “bush in the desert that doesn’t sense the coming of good” and

- a “tree planted by waters…that does not sense the coming of heat.”

These images are offered to illustrate a curse for “the individual who trusts in mortals” and a blessing “for the individual who trusts in God” (Jer 17:6,8). And the images seem pretty unchangeable:

The bush in the desert

The one who turns away from God seems in a terrible, lonely spot, like a “bush in the desert”:

“He shall be like a bush in the desert,

Which does not sense the coming of good:

It is set in the scorched places of the wilderness,

In a barren land without inhabitant”. — Jer 17:6

Image description: scrub bush, alone in the sand. credit: Benmansour Zakaria via Pixabay.com

The tree by the waters

The one who trusts God seems to be set for the long-term:

“He shall be like a tree planted by waters,

Sending forth its roots by a stream:

It does not sense the coming of heat,

Its leaves are ever fresh;

It has no care in a year of drought,

It does not cease to yield fruit. “– Jer 17:8

Image description: Tree, with many vibrant leaves, near, flowing rocky creek.

credit: V. Spatz, taken in Deanwood neighborhood of Washington, DC (2017-ish)]

Jeremiah’s separate bush and tree images might suggest that everyone is stuck with their own situation, reaping rewards for choosing God or left to overcome our own desolation for choosing wrongly.

But are we really meant to enjoy or struggle all alone?

Like a lot of the Book of Jeremiah, the ideas in this passage flip between extreme threats and promises. The People are warned to give up on “lies, no-gods, and things that are futile and worthless” (Jer 16:19) — or else. They’re also told there are many resources for people who seek divine guidance, from the “Fount of living waters [m’kor mayim chayyim]” (17:13).

Maybe Jeremiah believed that individuals can somehow turn, on our own, from “futile things” to trusting God. And that, with divine assistance, we can then move — as individuals — from curse to blessing. Or maybe Jeremiah didn’t see individuals as separate from community. In either case, later Jewish tradition leans heavily toward communal experience, collective prayer, and joint responsibility…. See also note above on how the last Torah portion in Leviticus is used to teach that Jews are responsible for each other….

The haftarah passage (Jer 16:19-17:14) concludes with a prayer:

“Heal me, Eternal One, and I will be healed;save me, and I will be saved. For You are my glory” — Jer. 17:14

This prayer suggests the possibility of change.

The passage doesn’t spell out exactly how change is supposed to happen, just the prayer: “Heal me.”

But it’s important to note that this haftarah is scheduled to be read every year right before the festival of Shavuot.

- Shavuot celebrates the giving of Torah.

- Torah is linked to water in Jewish tradition.

- That Fount of Living Waters is part of the healing work.

We know that “scorched places in the wilderness,” without anyone around, are harsh spots in which to pursue healing. Meanwhile, we know that some people in Jeremiah’s vision have access to water and fruit. But Jeremiah’s language hints at how change might begin:

The bush in the desert

The bush is shakhan — forced to settle

chareirim…m’leichah — scorched and salty places

after yasur — departing from, turning aside — from God.

The bush ends up bamidbar — in the wilderness— which can also mean “in the words.”

The tree by the waters

The tree is shatul — planted or transplanted

al mayim v’al-yuval — near water and streams

after yivtach — trusting, lying down in front of — God.

The tree sends out sharashav — its roots — the same term used for plants and words.

The bush seems an accidental location arrived at when someone loses the way. Maybe lost in a mess of words without any sense of purpose or meaning.

The tree, on the other hand, is carefully placed in a spot where it can thrive. It has the opportunity to send out roots and find what is needed.

The festival of Shavuot brings us all together — in spirit, if not in physical gathering — in the giving of Torah. If we share the bits of Torah that we have, we can contribute to something larger. Learn. Make connections. Building together toward a better world.

As a whole, this haftarah suggests that there is abundance, and there is great need. Too many among us are forced to settle in scorched and salty places, where survival is a struggle and words are not enough. Those of us with fewer barriers to places where our roots can find fresh water have to do better at making sure that we ALL (re-)connect with the Fount of living waters.

-#-